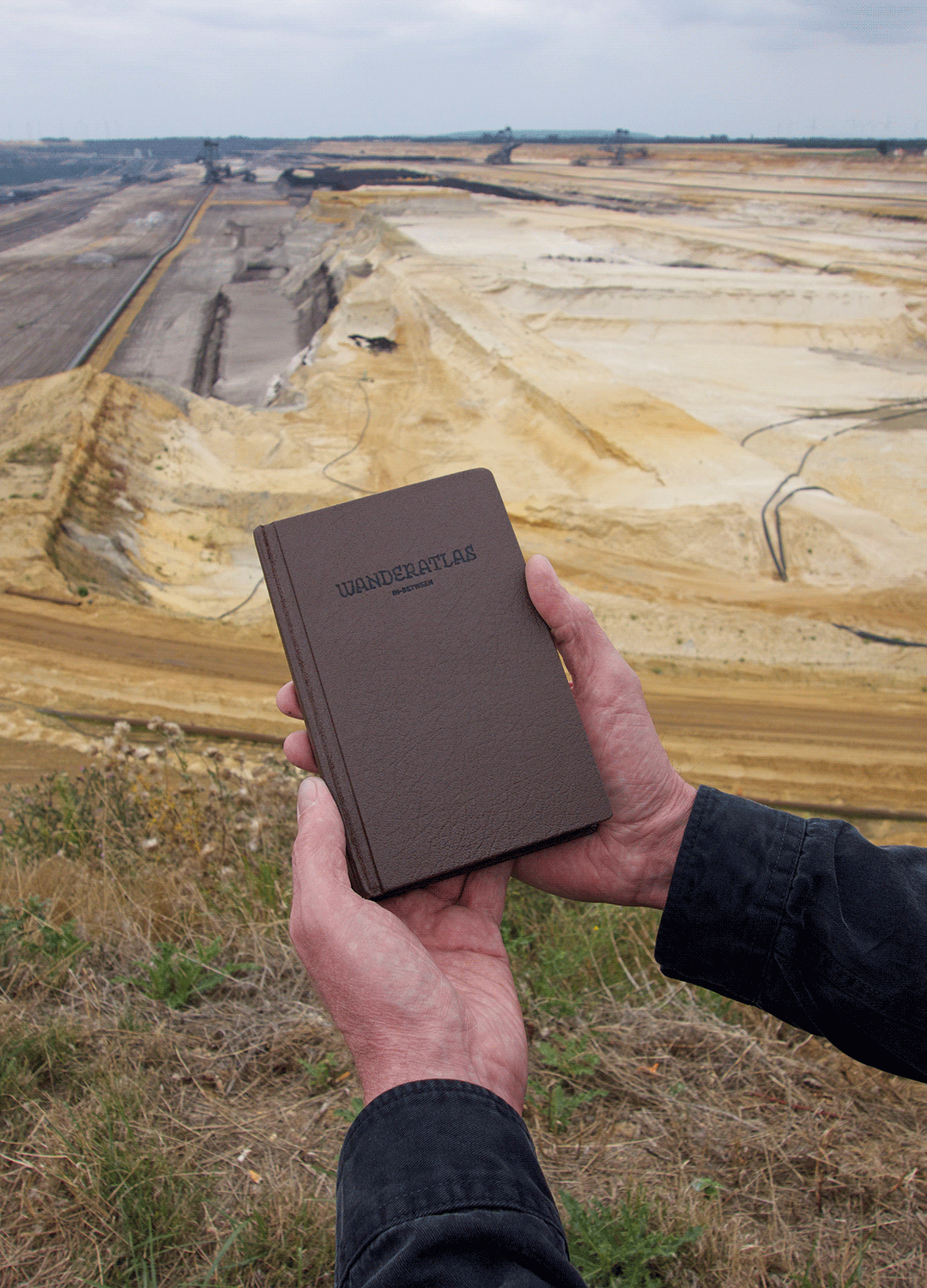

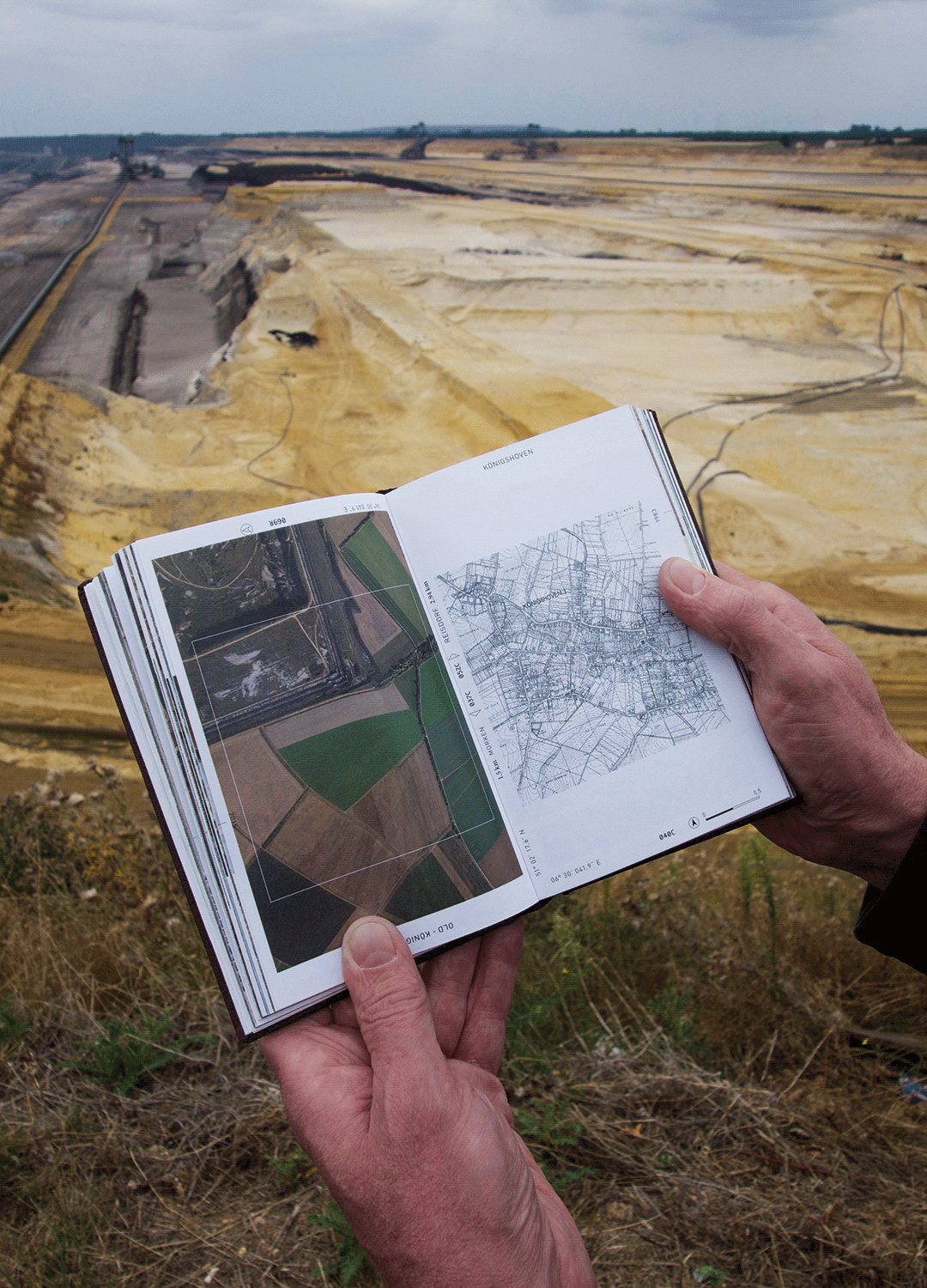

THE ATLAS OF THE IN–BETWEEN The wanderatlas shows 2 routes, based on the current state of affairs ( June 2015 ) : The Cultural Route shows the mining district "Garzweiler II" before the wandering of the brown coal mining hole [ 1955 – 2045 : From the past to the future past ]. The Re-Cultural Route shows the mining district "Garzweiler II" after the wandering of the brown coal mining hole [ 2045 – 1955 : From the future to the past future ]. Germany’s federal government approved Garzweiler II in 1995 in order to provide a constant supply of energy for the common interest. Independence of foreign supplies was a major argument for federal politicians to approve a substantial extension of the existing mining area, up-to 4.800 hectares until 2045. This means human and nature have to give way to the extraction of brown coal. Affected by this process are: 15 historical towns, about 7.000 re-settlers and the nature. Animals and insects are relocated. Infrastructure and rivers have to be redirected. The mining hole is situated in the middle of a system of numerous, concentrically arranged pumping stations. They keep the mine dry, but also affect the largest groundwater reservoir of Germany. Ecological systems, age-old landscapes and social entities such as families, communities plus the notion of home are put under enormous stress and strains. For all these consequences, the energy company RWE offers compensation. People can resettle to new villages and houses. After the mining machines have worked their way to a new territory, what’s left could be described as ‘Ground Zero’. An artificial-functional area is structured. RWE creates new farmlands and ‘recreational areas’, and nature has to start from scratch. Many and multifaceted interest groups are involved. Some parties claim that the affected area is a priceless and irreplaceable cultivated homeland; for others it is a valuable resource. Now, where the digger is, there had been my little village. There were old big trees, beautiful gardens, narrow streets. And on the right of the digger - around 200 meter behind it - there had been the house where my parents lived. Garzweiler II is located in the most densely populated and urbanized area of Germany. The economical utilization of brown coal as a resource has a history of almost 200 years in Germany. It provided the foundation for Germany’s industrial history and shaped the area, networks, traditions and people. Since then times have changed. Brown coal is one of the most inefficient energy resources. The emissions and different parties cast serious doubt on the sustainability and necessity of “Garzweiler II“. German brown coal mining has become a global issue. ‘The Wandering Hole’ sketches out the issue and urgency of finding a clarifying consensus. It conveys the extent and relative magnitude of an economic phenomenon and the emotional and ecological drama connected to it. RWE created dependency: As an employer, as a supplier and as a re-constructor. When the government approved Garzweiler II in 1995 a project was set in motion that can’t be simply brought to a halt. At a speed of 2,3 cm per hour the hole ‘wanders’ – as RWE calls it – through the landscape,resulting in a long-lasting process of transformation. Inhabitants have to deal with the consequences on a daily basis. They live in an in-between condition. Trapped between old and new. In-between recollection and hope. In-between loss and gain. In-between consent and protest. In-between independence and dependence. In-between questioning and clarity. In-between here and there. In-between was and will be. In-between past, present and future tenses. The uncertainty makes the process emotional and any frustration understandable. Until now the route of the hole is clear. So far, Garzweiler II is still moving ahead – by half a meter a day. Yet, it remains unclear how far the mining hole will wander. Here, Germany’s federal government has the final say.